In brief

Australian boards and senior executives are expected to maintain oversight of risk and compliance issues including legal, commercial, political and reputational risk issues. In-house counsel perform a central role in supporting this oversight and maintaining compliance. In the third of a five-part series, Partners Rachel Nicolson and Peter Haig, Senior Associate Chris Holland and Associate Freya Dinshaw look at the key questions that Australian boards and senior executives should be asking about the security of their foreign investments in 2017.

Jump To

- What is happening in international trade and investment in 2017?

- Are your company's foreign investments protected by Australia's investment treaties?

- David & Goliath… how can my company enforce its treaty rights against a State?

- Can you restructure to increase the prospect of obtaining effective treaty protection?

- Does your business consider applicable investment treaty protections as part of its due diligence when considering acquisitions or projects overseas?

What is happening in international trade and investment in 2017?

The year started with the dramatic exit of the US from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), the proposed free trade agreement (FTA) between Australia and 11 other trade partners. The fate of the TPP remains uncertain – the remaining 11 members held talks about the future of the trade deal in mid-March, and talks are to continue in May at an Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation meeting in Vietnam. The TPP is just one part of the story, but its demise would arguably represent a movement toward more inward-facing economies. Against this trend, on 15 February 2017, the European Parliament approved the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement between Canada and the European Union (known as CETA). At least four other investment treaties have also been signed this year.

In Australia, the Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade References Committee recommended that the Commonwealth defer from undertaking binding treaty action until the fate of the TPP becomes clear. However, Australia continues to negotiate other FTAs, hosting the sixth round of negotiations on the Indonesia-Australia Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement in February 2017, and is set to participate in the eighteenth round of negotiations on the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (the 10 ASEAN member states, plus China, India, Japan, South Korea and New Zealand) in May 2017 in the Philippines.

It remains to be seen whether 2017 will see more Australian companies seek recourse to international arbitration to resolve disputes with foreign governments. The recent decision of an arbitral tribunal in favour of an Australian company, Tethyan Copper Company Pty Limited (TCC), highlights the potential benefits of investment treaty protections to Australian companies abroad. On 20 March 2017, an arbitral tribunal found that Pakistan violated the Australia-Pakistan investment treaty in relation to an application for a mining lease by TCC's local operating subsidiary that was rejected by the Government of Balochistan. A ruling on damages in this case is expected next year.

Are your company's foreign investments protected by Australia's investment treaties?

Many companies operate in countries in which there is considerable political risk. This risk manifests where a host State takes action that adversely affects the investment of a foreign investor. The security of foreign investors even in 'low risk' countries, like Australia, has recently been called into question by government actions that have been criticised by some as capricious or rash. Such activity heightens the need for businesses to consider how secure their investments are from the adverse actions of foreign governments.

If your business operates or invests in a country that has entered into an investment treaty with Australia, your company may benefit from a number of significant protections as set out in the relevant treaty. The protections vary, but typically include:

- compensation if the host State seizes your property or unfairly limits the ways you can use your property;

- safeguards for the durability of any contracts you hold with the State or State-entities;

- compensation if you are unfairly targeted by new laws or regulations; and

- guarantees that you will be treated as well as the host State treats local businesses or investors from other countries.

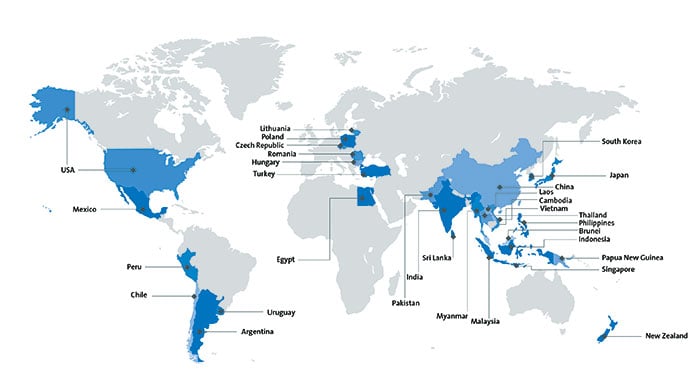

Australia currently has a broad network of investment treaties containing some or all of these protections. According to DFAT, Australia has entered into 21 bilateral investment treaties (BITs) that are currently in force,1 with each of: Argentina, China, Czech Republic, Egypt, Hong Kong, Hungary, India,2 Indonesia, Laos, Lithuania, Mexico, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Romania, Sri Lanka, Turkey, Uruguay and Vietnam. Australia has also entered into 10 FTAs containing investment chapters, namely, with Chile, China, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand, the US, and ASEAN.3

Figure 1: Australia's FTA/BIT coverage

In order to qualify for protection under one of Australia's investment treaties, your business will need to satisfy the jurisdictional requirements set out in the treaty – typically, as an 'investor' with an 'investment' in the host State. To be an Australian 'investor', your company will need to be a 'national' of Australia. This will generally require the company having been incorporated in Australia (and typically includes companies controlled by an Australian company). What constitutes a qualifying 'investment' is generally defined broadly, to include assets, property and intellectual property rights, loans, shares, rights under a contract or law to engage in certain activities, and activities associated with investment.

David & Goliath… how can my company enforce its treaty rights against a State?

Companies may not consider the courts in the host country of their investment to be an independent and appropriate forum for the resolution of disputes with the host government. Accordingly, the vast majority of Australia's investment treaties provide for disputes between investors and the host State to be resolved through international arbitration (commonly referred to as investor-State dispute settlement, or ISDS). Actions by the State that violate the terms of the treaty (typically, actions that are discriminatory, arbitrary, or that substantially lessen the value of your investment) may trigger an investment treaty claim. These claims can generally be enforced by investors through international arbitration.

Where an investor considers that their rights have been infringed, they are automatically entitled to pursue ISDS by virtue of their corporate nationality – there is no need for a company to have any direct agreement to arbitrate with the host State. Rather, the ISDS clause in the treaty will list the dispute resolution options available to an investor, which typically include arbitration before the International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), and/or arbitration under the UNCITRAL Rules. Even if a company decides not to commence arbitral proceedings pursuant to an ISDS clause, being aware of the company's rights can be of significant value in negotiating with the host State.

There are considerable enforcement advantages in the event that an investor receives a favourable award from an arbitral tribunal. An ICSID award is binding and is to be enforced as if it were a final judgment of a court in the host State. An investor may seek enforcement in any State that is a party to the ICSID Convention (not just the host State). Non-ICSID awards are subject to the national law of the place of enforcement and the New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards (the New York Convention). The New York Convention permits investors to enforce an award against assets located in any other State that is a signatory to the New York Convention.

Can you restructure to increase the prospect of obtaining effective treaty protection?

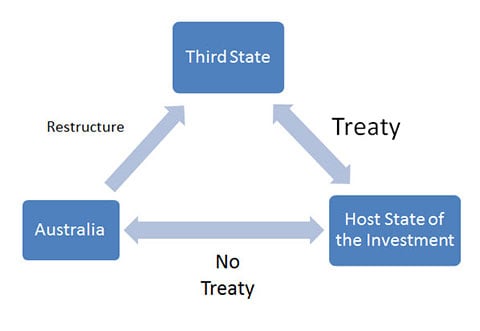

There are two instances where an Australian incorporated company may wish to restructure a foreign investment to gain effective treaty protection. First, where the business considers there to be political risk and Australia does not have an investment treaty with the host State of the investment. Second, where the business considers there to be political risk and the terms of Australia's investment treaty with the host State are limited or do not include access to ISDS.

Arbitral tribunals have recognised that restructuring investments in order to protect against breaches of rights by government authorities in a host State (through gaining access to ICSID arbitration) is a 'perfectly legitimate goal' as so far as it concerns future disputes.4 However, in relation to pre-existing disputes, it is likely that any attempt to restructure to gain jurisdiction under an investment treaty would be considered to be an abuse of process, and on that basis a tribunal would refuse jurisdiction. This raises the difficult question as to whether a particular dispute qualifies as a 'pre-existing' dispute. Tribunals have focused on the concept of foreseeability to make this determination – such that restructuring an investment will constitute an abuse of process when the investor restructures at a point in time when a specific dispute is foreseeable.

In terms of the mechanics of restructuring, this may be achieved by channelling an investment in the host State through a subsidiary based in a State which is a party to an investment treaty with the host State. As the terms of every investment treaty are different, this must be done carefully to ensure that the investment treaty contains sufficient protections. Importantly, the viability of any efforts to restructure to secure ISDS protection will depend on the treaty. If successful, restructuring may effectively provide your business with an additional level of insurance against political risk. This may provide valuable comfort for the business and assist in making the decision to invest in new markets.

Does your business consider applicable investment treaty protections as part of its due diligence when considering acquisitions or projects overseas?

Investment treaty considerations should form part of the due diligence conducted when your business is considering acquiring a foreign company or investing overseas. This may arise in a number of ways.

- Particularly if your business is considering investing in a country it considers carries high political risk, the due diligence conducted on that asset or project should include consideration of the applicable investment treaty protections.

- Where your business is looking to acquire a target company, its due diligence should extend to considering the investment treaty protections that the target company has available to it in order to protect its own assets and investments. This may enhance your understanding of the risks associated with the target company, and impact on the perceived value of the asset.

- Businesses with significant foreign investments may benefit from an investment treaty 'audit' – assessing what protection is available to the company's investments across the globe, to identify any assets vulnerable to political risk with a view to restructuring before any dispute arises.

Where existing protections are limited or do not include access to ISDS, it may be beneficial for the company to consider restructuring. Front-end investment treaty due diligence is an important part of understanding the risk profile of a foreign investment, and maximising available protections to mitigate against political risk.

Footnotes

- Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 'Australia's Bilateral Investment Treaties' (10 February 2017).

- India unilaterally terminated this BIT on 23 March 2017. The provisions of the treaty will continue to apply to investments made on or before 22 March 2017 for a period of 15 years.

- Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 'Status of FTA negotiations'. Australia's FTA with ASEAN and New Zealand is known as AANZFTA. The parties to AANZFTA are Australia, New Zealand, Brunei, Myanmar, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Vietnam, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Indonesia.

- See: Mobil Corporation, Venezuela Holdings, B.V., Mobil Cerro Negro Holding, Ltd., Mobil Venezolana de Petroleos Holdings, Inc., Mobil Cerro Negro, Ltd., and Mobil Venezolana de Petroleos, Inc. v. Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, ICSID Case No. ARB/07/27, Decision on Jurisdiction, 10 June 2010, para 204.