In brief

Although Trident Foods was unable to demonstrate use of its TRIDENT trade marks during the relevant period, for lack of actual control over its parent company, Justice Gleeson considered that the residual reputation in the marks meant that it was in the public interest to keep them on the Register. Trade Marks Attorney Jules Thai and Trainee Trade Marks Attorney Thomas Campbell report.

Background

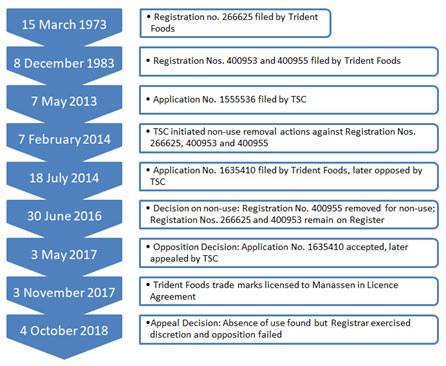

This is the third decision in an ongoing trade mark feud between Trident Seafoods Corporation (TSC) and Trident Foods Pty Ltd (Trident Foods) over the right to use the word mark TRIDENT for seafood products. A timeline of developments is provided below.

The decision

TSC was unsuccessful in its attempt to remove Trident Foods' registration nos. 266625 and 400953, despite establishing non-use during the relevant period. However, TSC had a minor victory in that it was partially successful in opposing registration of Trident Foods' pending application, with the application allowed to proceed to registration for limited goods.

Actual control of trade mark

TRIDENT-branded products have been sold by Trident Foods' parent company, Manassen (but not Trident Foods), since 2000. However, it wasn't until 2017 (after the Registrar's first decision and the relevant period) that Manassen was authorised by a formal licence agreement to use the trade marks. This licence was not retrospective, and the evidence was insufficient to demonstrate that Trident Foods had exercised quality control or financial control over Manassen during the relevant period. Therefore, Justice Gleeson held that there had been no actual control or use, within the meaning of section 8, by the registered owner during the relevant period. Instead, Her Honour exercised the discretion under s101(3) to keep the two Trident Foods registrations on the Register.

Discretionary power under s101(3)

Section 101(3) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) provides that the Registrar or court may decide that a trade mark should not be removed from the Register even if non-use has been established. In exercising the discretion, Justice Gleeson highlighted the following relevant considerations.

- Trident Foods had since entered into a written licence agreement to formalise Manassen's use of the TRIDENT mark, and that included a quality control clause to ensure Manassen uses the trade marks under the control of Trident Foods – ie as an 'authorised user' under the Act.

- There were sales of the relevant goods by Trident Foods bearing the trade mark after the relevant non-use period. Her Honour accepted that the sales were likely motivated by the non-use application, but nevertheless accepted this evidence because there was no argument that the sales were unprofitable or sold on an uncommercial basis.

- Trident Foods had an intention to use the mark on goods covered by the registration; if there had not been any intention to use it on the goods as registered, the Register's integrity would be diminished.

- Consumers are likely to identify the mark as coming from a group of companies of which Trident Foods is a member, and the long-standing use of the trade mark by Manassen took place with Trident Foods' knowledge and permission.

- Removal of Trident Foods' registrations and subsequent use of TSC's mark would be likely to cause confusion among consumers in the marketplace, due to the reputation of the TRIDENT mark created by Manassen's use.

This decision illustrates that a successful application for removal for non-use is no certainty – even if the appropriate grounds are established. Her Honour's considerations of public policy and the parties' conduct after the relevant non-use period are worth bearing in mind when considering the prospects of a non-use removal application.