In brief 7 min read

The recently launched Hague Rules on Business and Human Rights Arbitration are an innovative framework for the resolution of business and human rights disputes through international arbitration. We look at how they operate and why companies might elect to arbitrate under the new regime.

Key takeaways

- The Hague Rules on Business and Human Rights Arbitration (the Hague Rules) are directed at addressing a perceived gap in remedies available to companies and their stakeholders in resolving business and human rights disputes.

- 'Business and human rights disputes' is not defined in the Hague Rules, although the commentary says the term should be understood 'at least as broadly' as under the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (the UNGPs).

- The Hague Rules are based on the 2013 Arbitration Rules of the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (the UNCITRAL Rules), a procedural framework for international commercial arbitration.

- However, the Hague Rules contain a number of innovative modifications intended to reflect the business and human rights context. For example, unlike commercial arbitration, the Hague Rules provide for a high degree of transparency of the proceedings, to which parties must expressly opt out.

- The novel nature of the Hague Rules creates uncertainty as to how the new regime will operate in practice. That said, there are clear benefits to the level of control and autonomy that a party may have over the arbitral process. Submission to arbitration may provide a firmer framework for the dispute, and avoid some of the volatility associated with litigating in national courts.

- Matters amenable to arbitration under the Hague Rules are likely to include enforcement of contractual human rights commitments (eg in a supply chain or development project), complaints escalated from operational level grievance mechanisms by local communities, and adverse human rights impacts arbitrated under ad hoc arbitration agreements.

- We also expect that claimant law firms and public interest groups will test how far the novel transparency arrangements and flexible provisions relating to multiparty claims enable more effective access for group actions, when compared with local courts.

Why do we need business and human rights arbitration?

The Hague Rules, launched on 12 December 2019 at the Peace Palace in The Hague, have been developed by the Business and Human Rights Arbitration Working Group (the working group), a private body of international lawyers and academics. The working group was concerned that a remedy gap existed in the implementation of the UNGPs.

The United Nations Human Rights Council endorsed the UNGPs in June 2011, and they have come to be seen as the authoritative standard by which companies can manage and mitigate their human rights-related impacts.

The UNGPs provide that businesses should:

- carry out human rights due diligence to identify any adverse impacts of their operations on human rights; and

- remediate any adverse human rights impacts they cause or to which they contribute.

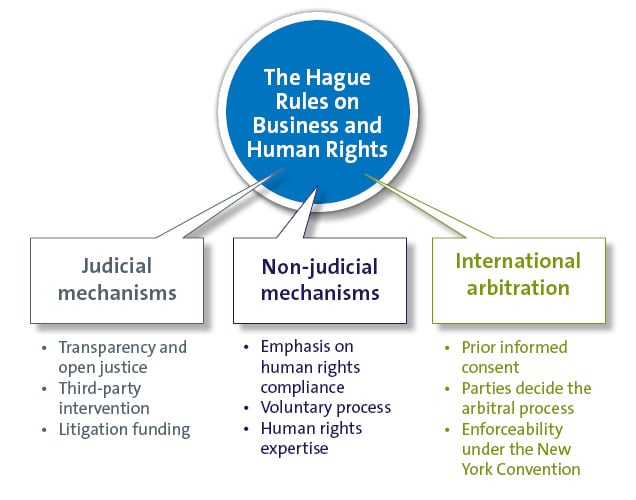

When it comes to remediation, the UNGPs distinguish between judicial and non-judicial mechanisms. Judicial mechanisms include the courts and labour tribunals, while examples of non-judicial mechanisms are national human rights institutions, international financial institution ombudsmen, and government-run complaints offices. One of the most popular non-judicial mechanisms for complainants has been the National Contact Points (the NCPs) set up under the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises.

The working group considers that these judicial and non-judicial mechanisms are deficient in resolving business and human rights disputes. This is because human rights-related disputes often occur in regions where national courts are 'dysfunctional, corrupt, politically influenced and/or simply unqualified'. Non-judicial mechanisms, such as the NCPs, are voluntary and cannot issue binding judgments.

In this context, the working group wanted to create an international private judicial dispute resolution avenue available to claimants and defendants. The Hague Rules are the result of this process.

How do the Hague Rules work?

The Hague Rules are based on the UNCITRAL Rules for international commercial arbitration. However, there are significant differences, which are set out in the commentary accompanying each article of the new Rules.

Like international arbitration, the Hague Rules:

- rely on the parties' proper and informed consent to arbitrate. Parties must show that they have entered into an arbitration agreement to resolve their dispute under the Hague Rules, whether in a contractual clause or after a dispute has arisen;

- allow parties to exercise their discretion to modify or opt out of certain provisions;

- follow an established process for the appointment of the arbitral tribunal and conduct of the proceedings;

- are not limited by the type of claimant or respondent to the proceeding; and

- opt in to the enforcement regime under the Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards (the so-called 'New York Convention').

However, in order to reflect the perceived characteristics of business and human rights disputes, the Hague Rules also differ quite fundamentally from international commercial arbitration.

For example, unlike international arbitration, the Hague Rules provide for a high degree of transparency of the proceedings. The drafting team has stated that this reflects the potential public interest in the resolution of these disputes, and the potential imbalance of power that may arise between parties. The transparency measures include:

- publication of critical documents, including the notice of arbitration and the response, the statement of claim and defence, listings of exhibits (such as expert reports and witness statements), orders, and any award(s);

- public hearings for the presentation of evidence and oral argument; and

- a broad degree of flexibility for the tribunal to arrange public access to hearings (such as video links).

The Permanent Court of Arbitration will act as a repository of all information published during the proceedings, and will publish information as a source of continuous learning.

The transparency regime automatically applies to proceedings under the Hague Rules, unless the parties have expressly opted out of the relevant provisions in writing.

In addition:

- interested third persons (such as NGOs) or states may apply to participate in the proceedings, on the basis that doing so would serve a public interest;

- the presiding arbitrator is required to possess specialised business and human rights expertise, and arbitrators must abide by a Code of Conduct;

- evidence gathering must be carried out in a rights-compatible and culturally appropriate manner;

- the tribunal must certify it is satisfied that its award is rights-compatible; and

- the tribunal may make orders for the disclosure of litigation funders, and the terms of funding agreements

By drawing on the UNCITRAL framework, the Hague Rules envisage a process familiar to parties that have engaged in arbitration previously. At the same time, the Hague process modifies the UNCITRAL Rules to reflect the peculiarities of business and human complaints, when compared with commercial disputes. In this way, the Hague Rules purport to provide a novel platform that is independent, expedient and certain – while also engaging the public in understanding alleged human rights abuses through an emphasis on transparency and open justice.

Why agree to arbitrate under the Hague Rules?

The novel nature of the Hague Rules creates some uncertainty as to how the new regime will operate in practice. When combined with the emphasis on public engagement and transparency, it might seem unlikely that companies would wish to opt in to the process.

That said, when threatened with litigation in a national court, there are clear benefits to the level of control and autonomy that a party may have over the arbitral process. Submission to arbitration may provide a firmer framework for the dispute, and avoid some of the volatility that can be associated with litigating in certain developing country courts. In addition, the Hague Rules offer a rights-compatible means of resolving disputes.

Examples of uptake of business and human rights arbitration by businesses include:

- a company seeking to enforce contractual human rights commitments as against a business partner (eg in a supply chain or development project);

- a company listing a referral to arbitration under the Hague Rules as the final port of call under an operational level grievance mechanism;

- parties incorporating arbitration under the Hague Rules into project/project finance documentation. The language would need to be worded carefully, to enable third parties to rely on the dispute resolution clauses despite potential privity of contract issues; and

- emergence of industry codes of conduct or accords stipulating arbitration in the event of alleged human rights abuses

We may also see states including arbitration under the Hague Rules as a dispute resolution mechanism in international investment treaties and agreements.

On the stakeholder side, complainants are pursuing increasingly novel means of resolving business and human rights disputes, in a range of national and international fora. We expect to see interest in testing the new regime, and in companies' appetites to arbitrate – with public pressure on companies to do so if eg the request for arbitration is made public.

The high degree of transparency incorporated into the Hague Rules should make it easier for parties to discuss their claims publicly, and thereby identify others whose rights may have been similarly affected. This, coupled with a flexible regime for joining third parties to proceedings, may make the Hague Rules a more convenient framework than traditional court litigation for the resolution of claims involving a large group or class of affected persons.

We expect that claimant law firms and public interest groups will be interested to test the extent to which the transparency arrangements and flexible provisions relating to multiparty claims enable more effective access for group claims, when compared with local courts.

Please let us know if you would like to discuss any of the issues raised in this Insight.