High Court provides guidance on mandatory labelling regimes 10 min read

Earlier this week, the High Court handed down its unanimous judgment in the Mitsubishi fuel consumption labelling case,1 finding in favour of Mitsubishi. The car maker successfully appealed an earlier decision that it had engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct because a customer's real-world fuel consumption levels exceeded those found on the mandatory label affixed to his vehicle at the time of purchase.

The High Court's reasons give much-needed clarity to all goods and services providers regarding the nexus between statutory labelling requirements and misleading or deceptive conduct under the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), and the protections afforded to them if they comply with their statutory obligations.

Key takeaways

- As a matter of statutory interpretation, the courts will look to read down general prohibitions in light of more specific ones.

- In keeping with this principle, strict compliance with mandatory rules (such as those for product labelling) may shield companies from findings they have engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct or other breaches of more general consumer protection legislation.

- Automakers and other manufacturers with mandatory labelling requirements can now breathe a sigh of relief that a new facet of class action risk has significantly diminished.

- The case also provides a salient reminder of the need for defendants to put forward robust evidence at the outset of strategic claims as further evidence cannot be led at a later stage.

Legislative background

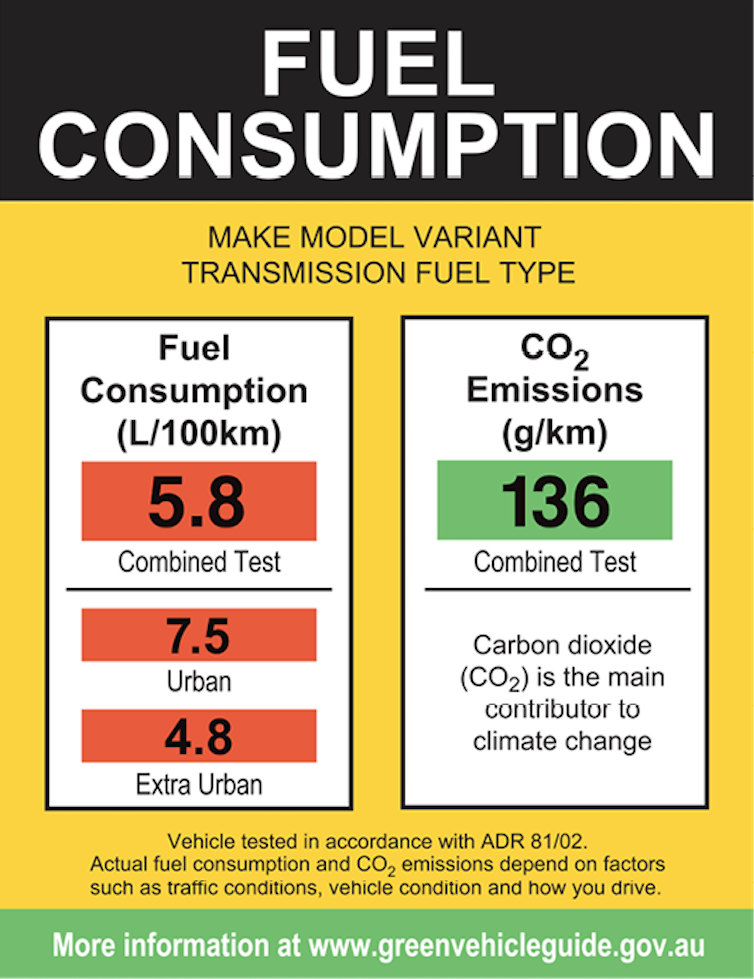

Under the Motor Vehicles Standards Act 1989 (Cth) (MVS Act) and a legislative instrument under that Act – the Vehicle Standard (Australian Design Rules 81/02 – Fuel Consumption Labelling for Light Vehicles) 2008 (Cth) (ADR 81/02) – a new vehicle sold in Australia must have a fuel consumption label affixed to its windshield in the following form (which will be familiar to many of you: see image).

The label communicates the fuel consumption per 100 kilometres of driving (in litres) in three different prescribed conditions: 'urban', 'extra urban' and 'combined'. The relevant tests are carried out in a laboratory under strict testing conditions prescribed by ADR 81/02, using a test vehicle of the same model car to which the label is affixed.

Section 18 of the ACL prohibits a person from engaging in conduct in trade or commerce that is misleading or deceptive, or is likely to mislead or deceive. In addition, the ACL contains a series of consumer guarantees which all goods sold in Australia to a consumer (as defined in the ACL) – including passenger vehicles – must meet. This includes the acceptable quality guarantee in s 54, which provides that goods will be of acceptable quality if they are as: (a) fit for purpose; (b) acceptable in appearance and finish; (c) free from defects; (d) safe; and (e) durable, as a reasonable consumer would expect.

Procedural history

VCAT

Mr Begovic, the owner of a 2016 Mitsubishi Triton, filed a claim before the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT) against Mitsubishi Motors Australia and the Mitsubishi dealer who sold the vehicle to him (collectively Mitsubishi), alleging that his Triton's real-world fuel consumption levels significantly exceeded the consumption displayed on the label. Around the time of bringing the claim, Mr Begovic's vehicle had been driven for nearly 50,000km.

Mr Begovic claimed that Mitsubishi had contravened both ss 18 and 54 of the ACL, in that the fuel consumption label was misleading or deceptive as it was inaccurate, and therefore the vehicle was defective and not of acceptable quality as required by the consumer guarantee.

As part of his claim, Mr Begovic adduced expert evidence of tests undertaken to his vehicle, which showed that its real-world fuel consumption when replicating the ADR 81/02 testing requirements was 26.6% higher for 'combined', 17.8% higher for 'urban', and 36.8% to 56.3% higher depending on the form of test used for 'extra urban', than the figures stated on the fuel consumption label. At VCAT, Mitsubishi did not put on its own expert evidence and Mr Begovic's expert evidence was accepted.

Mr Begovic succeeded on both claims at VCAT, with the dealer ordered to buy back Mr Begovic's vehicle.

Supreme Court of Victoria

Mitsubishi obtained leave to appeal the VCAT decision to the Supreme Court of Victoria. The principal challenge was, in essence, whether a manufacturer required to apply a fuel consumption label to a vehicle – the form and content of which are prescribed by law – could engage in misleading or deceptive conduct contravening s 18 of the ACL when real-world results differed. Mitsubishi also challenged the finding that it had breached the consumer guarantees under s 54.

As Mitsubishi had not challenged Mr Begovic's evidence at first instance it was unable to challenge it subsequently.

The Supreme Court allowed Mitsubishi's appeal in respect of the consumer guarantees. Justice Ginnane found that a breach could not be made out because VCAT did not find that Mr Begovic's vehicle was actually defective. However, his Honour ultimately dismissed Mitsubishi's appeal in respect of the misleading or deceptive conduct claim, concluding that the fuel consumption label was effectively a representation by the manufacturer that – if the particular vehicle it was affixed to was tested in accordance with ADR 81/02 – the results for that vehicle's fuel consumption would be similar to or substantially the same as the label. Because of the variation between Mr Begovic's test results and those stated on the label, Mitsubishi had engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct.

Victorian Court of Appeal

Mitsubishi appealed Justice Ginnane's decision to the Victorian Court of Appeal, but was again unsuccessful in overturning the findings on s 18. While the Court of Appeal agreed that the label accurately represented the results of the ADR 81/02 testing, it found that there was still misleading or deceptive conduct in contravention of s 18 due to the differences in the results obtained by Mr Begovic.

Following this, Mitsubishi sought and was granted special leave to appeal to the High Court.

Judgment details

Overview

Mitsubishi appealed to the High Court on two grounds:

- that performing the ADR 81/02 test and affixing the prescribed label was 'mandatory conduct', and that s 18 of the ACL did not apply to mandatory conduct; and

- that the label did not represent that the results of the test were replicable; rather the label only showed the results of ADR 81/02 testing on a test vehicle of the relevant type at a particular time.

The High Court found that the first ground was made out, such that it did not need to consider the second ground. In light of this finding, Mitsubishi succeeded in setting aside the orders of the lower courts, and dismissing Mr Begovic's application to VCAT.

Mandatory conduct ground

The essence of Mitsubishi's first ground was that Mitsubishi (and its dealer) could not have breached s 18 of the ACL as they were merely complying with the MVS Act's requirement to affix a prescribed label. To put this another way, Mitsubishi did not freely choose the representation on the label or the circumstances of the testing – these were matters that Mitsubishi was mandated to carry out in accordance with the government's legislated requirements.

The Court of Appeal had previously rejected this argument, holding that the MVS Act and ADR 81/02 did not require Mitsubishi to offer a vehicle for sale in circumstances where the representation on the label was misleading – in essence, Mitsubishi could simply have chosen not to sell the cars. However, the High Court gave this short shrift, finding that s 18 presumes a choice to engage in trade or commerce. Not only was Mitsubishi bound to apply the label in order to import the vehicle into Australia, its dealer was also bound to ensure it remained as a safety standard in order not to contravene s 106 of the ACL.

The High Court went on to rely upon an earlier decision of the Court in R v Credit Tribunal; Ex parte General Motors Acceptance Corporation (GMAC).2 GMAC concerned analogous circumstances involving the concurrent operation of a predecessor to s 18 of the ACL, and a state law requiring that a certain type of notice be given by a credit provider to consumers, which was ultimately found to be inaccurate. The High Court held that, like in GMAC:

[t]he unexpressed assumption which underlies the prohibition … is that the conduct ... is not conduct in which the corporation is required to engage by, or under the compulsion of, some other law enacted in the interests of consumers.

In other words, as a matter of statutory construction – when faced with an inconsistency between two pieces of legislation, such as the MVS Act and the ACL – the court is required to attempt to reconcile the two. Further, in doing so, a court will generally seek to read down more general prohibitions (such as those concerning misleading or deceptive conduct) in light of more specific ones (such as particular labelling requirements).

It was also important to the court's decision that neither Mitsubishi nor its dealer had engaged in any positive conduct other than affixing the label to the vehicle. That is, they did not make any further representation that the actual vehicle being sold conformed to the ADR 81/02 test results.

Implications

Strict compliance with specific provisions

The High Court's reasons give a degree of protection to automakers and other manufacturers that compliance with labelling rules and other forms of mandatory conduct will not expose them to findings of contravention of consumer protection regimes, such as those for misleading or deceptive conduct.

However, in reconciling the tension between the MVS Act and the ACL, the High Court read down the latter only insofar as Mitsubishi engaged in conduct it was 'required to engage [in] by, or under the compulsion of, some other law'. Had Mitsubishi not strictly complied with the MVS Act and ADR 81/02 requirements, it seems doubtful this carve out would have applied. Likewise, had Mitsubishi made further representations as to the fuel efficiency of its vehicles, these may well have fallen foul of s 18.

It therefore remains important for suppliers and manufacturers to consider carefully the terms of any labelling or other mandatory regimes and pay close attention to adhering to their particular requirements. Any further representations to be made to consumers beyond the contents of the prescribed label should be carefully vetted for accuracy, and qualified where appropriate, in accordance with usual processes.

Class action risk

The High Court's findings will likely be a major blow to the class action that had been launched against Mitsubishi Australia on behalf of some 70,000 Mitsubishi Triton owners, making similar allegations of breaches of ss 18 and 54 of the ACL off the back of Mr Begovic's initial success.

The ramifications of the High Court's decision will extend beyond automakers to all manufacturers and suppliers of goods that are subject to mandatory labelling regimes – including food, beverage and appliance providers. Had Mr Begovic's claim succeeded, there was a real prospect of related proceedings being commenced across a variety of sectors – wherever real-world results deviated from those mandated to be stated on the label – with associated class action risk. While manufacturers should remain alert, there is now less need for alarm.

Evidence

Another important takeaway from the procedural history of this matter is the need for companies to give due consideration to the evidence put on in the early stages of litigation, especially in the setting of strategic claims.

While Mitsubishi may be forgiven for not appreciating the significance of Mr Begovic's case before VCAT, or the class action and appeals it would spawn, there is no doubt that Mitsubishi was encumbered during the appeals by its decision not to adduce any expert evidence at the outset.

This meant that Mitsubishi was unable to challenge circumstantial aspects of Mr Begovic's claim that may have had an impact on his test results, including the age and condition of Mr Begovic's car, which had travelled some 50,000km. Had this evidence been adduced, it may have strengthened Mitsubishi's prospects of succeeding at an earlier stage in the various appeals.

Footnotes

-

[2023] HCA 43

-

[1977] HCA 34